October 9, 2000, Rutland Herald Business Monday

INSIDE OMYA: A look at one of the region's oldest and most vital industries

October 9, 2000, Rutland Herald Business Monday

INSIDE OMYA: A look at one of the region's oldest and most vital industries

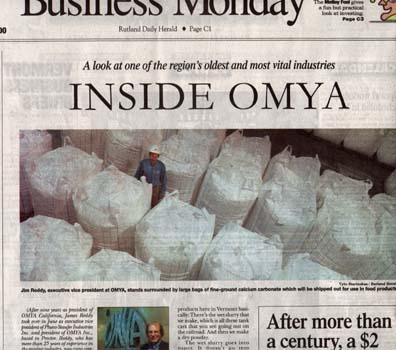

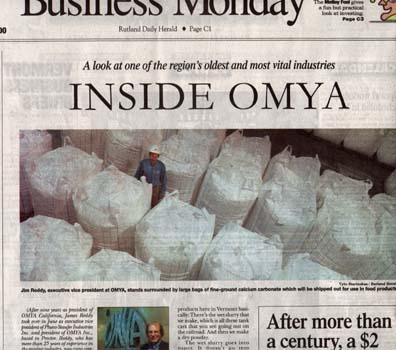

(After nine years as president of OMYA California, James Reddy took over in June as executive vice president of Pluess-Staufer Industries Inc. and president of OMYA Inc., based in Proctor. Reddy, who has more than 25 years of experience in the mining industry, now runs company operations in North America. John Mitchell, who had been running OMYA Inc. here, will retire in a year or two. He stays on as treasurer of Pluess-Staufer and an executive vice president of OMYA. Reddy recently sat down for an interview with Herald Assistant Managing Editor Stephen Baumann and business columnist William Hahn.)

James M. Reddy

Age: 56

Born: Springfield, Mass.

Position: Executive vice president of Pluess-Staufer Industries, president of OMYA Inc.

Education: BS in mechanical engineering from Case Western Reserve University, MBA from Northwestern University

Residence: Mendon

Married, with two daughters, three grandchildren

Hobbies: Hiking and camping, especially in American wilderness

Question: Your company's structure can be confusing, OMYA, OMYA West and OMYA Arizona and whatnot. Give us a rundown of how the company is structured and how Vermont figures into it.

Reddy: The parent company is OMYA AG, and the headquarters is in Switzerland. We're in approximately 40 countries around the world.

Generally, in most countries, the way the company is organized a country would be organized as a company. So we have a company in France, a company in Korea. For a reason I never bothered to ask, but I'm just assuming they came to America said 'jeez this is a big place,' we tended to organize it slightly different over here, and it's almost that each state and each operation is a separate company because the distances are so far apart. But there's a parent company and a couple of operating divisional headquarters. The parent is in Switzerland; one operating company divisional headquarters is in Proctor, Vt., and that's for the Americas. Recently we split off the Pacific Rim and their headquarters is in Australia. We have two companies here essentially. There's a company called Pluess-Staufer Industries. Right now, I'm executive vice president of Pluess-Staufer Industries. We are the parent company of OMYA California, OMYA Inc. (That's here in Vermont), OMYA Arizona and OMYA Illinois. Pluess-Staufer is technically the non-operating parent. We have OMYA in Switzerland, OMYA in Vermont and then a bunch of companies under that, and we have another company in Australia, and companies reporting to that. Rutland, Vt., is one of the three key locations. Basically, we do exactly the same thing all over the world. We're in the calcium carbonate industry. That's all we do. We make find and ultra-fine white powder, which is in all that paper you're writing on.

Question: You're 99.8 percent in calcium carbonate. Used for

Reddy: We make two lines of products here in Vermont basically: There's the wet slurry that we make, which is all these tank cars that you see going out on the railroad. And then we make a dry powder. The wet slurry goes into paper. It doesn't go into newsprint -- so far we haven't convinced the newspaper industry to do that. It does go into the higher quality stuff.

Question: It's essentially a whitener?

Reddy: It's two things: It's primarily a whitener. It also gives the paper better qualities. Just 100 percent wood fiber is a flimsier paper. If you leave it laying out in the sun for a half-hour before you pick it up, it turns yellow. That's because it's acid-based. Our company actually developed a process in the '60's to convert from an acid plant. Calcium carbonate is an antacid, it's what you eat for an antacid tablet -- Tums, Rolaids, Maalox -- that's calcium carbonate, we make that stuff. Antacid reacts with acid, so you can't put calcium carbonate in acid paper or it just dissolves. So they had to convert the paper process our company developed it, and we're kind of proud of it because it means the paper mills are much more environmentally friendly. They have to be. The acid-based paper is what goes out in the stream. And because of the white calcium carbonate you stop bleaching the paper with chlorine, so there's no more dioxin. The end result is you've got paper that's not acid-based anymore. I collect old books. You get a book from the 1860, it's brittle, it'll fall apart. You get a book from 1500 and it looks like it was just put in yesterday. They didn't used to make cheap acid-based paper 300 years ago, so the paper from 300 years ago is better than when they went to the acid-based stuff. The stuff that we're printing now -- the Xerox piece of paper you've got right there -- it's going to last 1,000 years again because it wasn't made with an acid base. It's made neutral and it's filled with calcium carbonate. So paper will last again. But that's the biggest product we make here. The biggest single industry is paper, that's all that white stuff.

Question: What percentage of your business would that be?

Reddy: At least 50 percent. And by the way, it also saves trees. Worldwide, about 15 percent of paper is calcium carbonate, so we're chopped down 15 percent less trees. High-quality paper like National Geographic, that's 40 percent calcium carbonate. What all our customers want is us to keep pushing the envelope and getting better brightness because the consumers want better brightness on their paper. And opacity.

Question: And it's more expensive?

Reddy: Yeah. You want better quality paper, generally you've got to pay more for it. But that's half the business. The other half is the dry stuff. And we take the same stuff wet and we dry it and then it goes into everything. The backing on your carpet is 85 percent calcium carbonate. There's a little latex back there to hold the fiber in, but the rest of it's carbonate. The paint on the wall is carbonate. You know, paint used to be lead-based. Well, they got rid of the lead because people didn't like kids eating the lead; it caused brain damage. So it's in paint, it's in joint cement, it's in these roof tiles, it's in the floor tiles. They took the asbestos out of the floor tiles and put calcium carbonate in. The advantage of calcium carbonate is that it's white, it's consistently white, it's environmentally, absolutely neutral, it doesn't harm anything. So everybody likes it because it's a white base and they don't get blotchy color. It doesn't react with anything, except acid. So then the other thing we use it for is an antacid tablet. It's also the calcium supplement -- any food that has calcium in it -- that's what this is. Chewing gum, for example, is 40 percent calcium carbonate inside the gum. Question: Is it the stuff in toothpaste that keeps your teeth whiter and brighter?

Reddy: Sometimes. Actually, I said it reacts with almost nothing. It reacts with fluoride. There are a couple of toothpastes that have figured out how to put it in. Without giving brand names, if you see a blue strip on the side so that you can see that the fluoride is separated away from the carbonate until you get it in your mouth, then they've figured out how they get the fluoride in, to keep it away so they don't react. It's in everything because it's so environmentally neutral. &Mac183;that's why they use calcium carbonate. But they want the highest purity, almost everybody wants the consistent white product so that everything you buy -- this batch of floor tile and that back of floor tile, they match up. We have really tight control on the color and particle size obviously. They need to have the same stuff. You just can't send lumps one time and powder the next, but color is the biggest thing because it has to match.

Question: What size is the company?

Reddy: We're a private company, so we don't give all these numbers out. In round numbers the problem is when you're in 40 different countries and with currencies fluctuating every day, to relate to a single currency is difficult. But we're not anywhere near a Ford, we're a couple billion dollar company in sales.

Question: In Vermont, which specifically concerns us, how much have you been growing in recent years?

Reddy: We've been growing pretty well. I'm not sure about Vermont. I know what the growth has been in North America. All our companies combined, we've been growing in the 10-15 percent a year range.

Question: Obviously, that's a factor of finding deposits elsewhere.

Reddy: We've acquired a couple of other companies that were interested in selling. We've opened two new plants in the 1990s, one in Alabama and one in Arizona. The Arizona plant is opening as we speak. The demand for our products is going up because it's replacing many other minerals that might go into something because it's so environmentally friendly. Environmental concerns are becoming more and more important, not just in Vermont, but throughout the whole country, and calcium carbonate, again, is probably the most environmentally benign mineral you can put into anything. And the process of making it is just grinding. There's no chemical reactions we're doing, it's a benign process in the manufacturing. So a lot of other people are switching from other things like talc, which take more processing, and replacing those with calcium carbonate. And we've had tremendous publicity in last two years, especially about the requirement for calcium in the body. Everybody knew about calcium for osteoporosis, but then about a year and a half ago there were studies that people who eat more calcium have less cancer of the internal organs -- I forget, it's the kidney, the liver and the pancreas, or something, you have less cancer -- so all of the mineral supplement people, everybody's just plastering calcium over everything.

Question: And what we have when we eats Tums, we're eating Vermont marble?

Reddy: I can't tell you. You know, it's really strange. Most of the food companies you go through the grocery shelf and I'll guarantee you there are some of the biggest brand names of cereals and foods. It's incredible, most of these pharmaceutical companies think they've got something that nobody else has and so we sign secrecy agreements with them. We agree we won't tell them, we won't let any of their competitors know who they're buying from. I'm not supposed to tell you brand names, but let me phrase it this way: You'll recognize all the names and there's nothing unfamiliar. We've got some of the biggest companies in America.

Question: Are there other firms doing this?

Reddy: Yes. Actually to be able to do this, you have to have the right kind of marble. A lot of people tend to think we are mining a common mineral. There are more gold mines in America than there are calcium carbonate mines. Gold is more common than the quality of calcium carbonate that we need. Because the stuff that we need, first off, you have to be able to eat it. It has to be very safe. It has to be very pure. So there aren't a lot of places where it's done. So I can do this pretty simply. There's a band of mineral that comes through Canada, right down through Vermont and Massachusetts, and actually goes down into Alabama. Only a few places on this band of the same deposit is it close enough to the surface that you can get. There's our company up in Canada, there's us in Vermont, there's a competitor (SMI Specialty Minerals in Massachusetts) and then down in Alabama again there's us and there's another competitor there. They're all mining the similar deposit at those places every few hundred miles where it crops up to the surface. In Illinois, there's another band along the Mississippi River. There's a competitor there, and there's us, OMYA Illinois. There's another deposit down in Texas. On the West Coast up in Canada there's another company. And another right across the border. And there's us again. And then down in southern California there's us and SMI again. That's basically it in North America.

Question: A question about geology, how the rock just happens to form in the earth.

Reddy: It takes a lot of weird conditions. Many people are familiar with limestone. You're familiar with coal and diamonds. Coal and diamonds are exactly the same thing chemically. What turns coal into diamonds is about 50 million years, about 1,500 degrees centigrade and the pressure of a couple miles of earth squeezing it together. That's what turns limestone into calcium carbonate. You need 30, 40, 50 million years, you need a couple miles of earth piled on top of it and you need about 1,500 degrees centigrade to cook and compress and squeeze and burn off all the impurities. And that doesn't happen in a lot of places in the world. Limestone and calcium carbonate are related they're different because of all the impurities and the form you find it in, but just like coal and diamonds, it's the same thing. You don't find it too many places. When you find it, it's a valuable deposit. Vermont is one of the few places in the country that has it. There is the long band, we know it lies between Vermont and Alabama but if it's buried so deep you can't even get to it. This isn't a product you can just go dig. You know, diamonds in South Africa you'll dig a mile underground to go find it. We can't go dig a mile underground to find this. So you have to find it where it's relatively close to the earth.

Question: Given the company's long history in Vermont, what do you see for the future?

Reddy: We have a lot of reserves. We've spent a lot of money building up the plant in Florence. When we bought it, it was a very small plant. It's now a very large plant. We've had it about 25 years. This is one of the key places in North America for finding a high-quality deposit. And we've got plenty to last a long time.

----------------------------------

October 16, 2000, Rutland Herald

Inside OMYA Part 2: Company puts on a new face for a changing world

http://rutlandherald.nybor.com/Business/Story/14122.html

(This is the second part of an interview with James Reddy, the executive vice president of Pluess-Staufer Industries and president of OMYA Inc., headquartered in Proctor. The interview was conducted by Herald Assistant Managing Editor Stephen Baumann and Business Monday columnist William Hahn in late September.)

Question: Has anyone figured out how many years supply of calcium carbonate is left? Like oil, we assume, there's only so much there.

James Reddy: When I was in college I wrote a paper on the availability of oil and there was a 20-year supply left in the world. When I worked for Swift, they bought an oil company and there was a 20-year supply left. There's always a 20-year supply of oil left. Calcium carbonate is not quite like oil. There's only limited deposits that are relatively accessible, but we know the band runs from here to Alabama. We can spend a little more and get it out of the ground. Compared to oil, our company takes a longer-term view and we have a lot of reserves.

Question: : You need more stone in order to grow, but there's been a lot of public resistance to expansion, especially the traffic impact. What do you do about that?

Reddy: We had a meeting down in Danby yesterday where that was one of the key issues people in the community were asking about. One thing we had done earlier this year was that we went down and talked to the people in the community to find out what their concerns were, and transportation was one of the key issues that came up. As part of the Act 250 process we're going through, one of the things we've done is we've told our consultant reviewing the whole thing that he should listen to the concerns of the people in the community and take a look at all the alternative ways of getting it from A to B. We need it out of the quarry. Here's where the deposit is. We have to live with where the deposits are and here's our plant. Figure out, if you can, some way to get it from here to there minimizing the impact and working with the system and the structure we have here in Vermont.

Question: : The problem up in Middlebury is with the number of truck trips. You had wanted a certain number and the Environmental Board allowed less. That kind of compromise hasn't been acceptable.

Reddy: : If the company is going to continue to grow, we need more material in the plant from one location or another. Obviously, if you're limited to that number of trucks and that's all that can come in, you don't grow anymore, or at least in this location you don't grow anymore. You stagnate.

Question: : OMYA's appeal of the Environmental Board decision limiting truck trips is now in the federal court? Other than simply winning the court case, do you see any resolution to this issue?

Reddy: : Right, it's in the federal court. The resolution of the case may be a solution. Well, it will give us an answer one way or the other (about) the north. But if we're going to continue to grow and continue to meet our customers' demands, we need more material at the plant.

Question: : Can you see any way of getting around the problem of your big trucks going through small towns?

Reddy: : Big trucks go through the small town now. Your trucks go through the small town. The trucks that deliver your newsprint go through the small town. Eighty-six percent of the businesses in Vermont rely on their trucks for 100 percent of their supplies. There are trucks on the road all day long that have nothing to do with us. You want to go to the grocery store and buy food, somehow the grocery store had to get the food there, and they come in big trucks. If you want to live here, if you want to go to the store and buy things, you want things delivered to your house, they come in trucks. It's a problem for Vermont. Vermont, on this side of the state, has a difficult transportation system. There is no good corridor other than Route 7, and Route 7 goes through small towns.

Question: : You understand how people would feel about more trucks rumbling past their doors.

Reddy: : I understand there's a lot of concern. We're trying to do what we can to address it and see if there are alternatives. One thing we do is most of our shipments go out by rail. Those that don't go out by rail, we're trying to constantly work with our customers to see if we can convert them to rail. The problem is some customers are too small to take rail; some customers are not on a rail siding. But actually to help the situation we set up what we call bulk transfer stations for the customers that are too small to take a rail car or are not on rail car lines, we ship bulk rail cars out to facilities located around the United States.

Question: : Like a depot?

Reddy: : Yeah, they take a rail car in and you can transfer from a rail car to trucks so that we can ship. We're trying to keep as many trucks off the road as we can; generally we just keep working in that direction. We're looking at making another big switch to try to get a lot more material that we ship out of the plant on rail so that we can minimize as much as possible. Most of our product already does go out by rail, but we're trying to get more and more out.

Question: : Is there any potential for using rail from the quarry to Florence?

Reddy: : That was looked at up in Middlebury. The problem is our quarry's on the east side of Route 7, then you've got 7 in between, you've got Otter Creek and then you've got the railroad, so it's a difficult situation. Also, we're looking at how can we get from here to there. Can we get to the rail somehow instead of having the rail get to us? That would help somehow if we could do that. We're constantly studying that. We're looking at that again right now.

Question: : Is the state working with you on this?

Reddy: : The state is amenable to what they can do, but they aren't By working with us, they're encouraging us, but they're not actively supporting us, so what can they do? They can tell us they'd like us to do that.

Question: : By supporting the effort with people and money?

Reddy: : They haven't done that so far. If you know somebody I can go talk to I'll be happy to.

Question: : Just an idea. They do have a development agency. Any creative solutions?

Reddy: : If we could find a creative solution that would be great.

Question: : But basically, it's up to you to find a creative solution.

Reddy: : So far. We're looking. It's not an easy one.

Question: : Do you have any timeframe for the court case?

Reddy: : I have a hard enough time predicting our own business, let alone the courts. It could go quickly or it could go forever.

Question: : How about the issues down south (with the proposed quarry near Danby Four Corners?) What does that look like?

Reddy: : We had a pretty good session last night. I don't think there were any questions asked that we hadn't already asked by going down and interviewing people in the community. The biggest issue again is the transportation issue, how do we get from the quarry through the roads in the towns there, assuming we go by truck. What we've told the people there is we've hired some outside experts as part of the Act 250 process and specific instructions are: 'OK, we've interviewed the people and here are the specific concerns they've expressed. Open your mind up and see if there's a way that you get from the quarry to the plant. Don't assume you have to start with trucks. Think of anything. Is there some alternative technology that you can use? Open your mind up and let's see what you can come up with.' So the process means that when you tell people to open their minds up and look at alternatives, you don't tell them, 'this is the answer I want to get.' We said, 'you guys figure it out, look at everything you can and come back to us.' It takes longer, because now you've told them look at all the possibilities.' So it's going to take a little longer. Now, I don't know what they're looking at.

Question: : But with the goal of getting from Point A to Point B?

Reddy: : We want to get from A to B, yeah. And we want to know what the concerns of the local community are.

Question: : So there could be alternative routes and alternative forms of transportation?

Reddy: : I said, the key was, 'don't limit yourself to trucks. Open up. Think. What are other people in other places in the world doing?'

Question: : There seems to be some question about this quarry being a strip mine. It's in a remote area.

Reddy: : I was asked that last night at the hearing, 'Is this a strip mine?' And this is not a strip mine. A strip mine, I've worked in strip mines before. I worked for a company that had strip mines when I was in the fertilizer industry and a very simple way to think of it is that a strip mine is a continuous process where you take a little bit of stuff off the top and you just keep on going, and you're continually opening up new areas. The mine I worked for in Florida was a phosphate mine and we mined 300 areas a year. Every year, we mined 300 new acres. That's half a square mile, 640 acres is a square mile. You know we're chewing up a big chunk. And you're also reclaiming behind it and we used to plant orange groves and we had a golf course we put in. I mean you could do a lot of stuff with it after you were done, but you are chewing up a lot of new territory all the time. The quarry we're looking at, that we'll be submitting the application for, actually the hole itself, the quarry itself, and it is a quarry not a strip mine, is 23 acres. There's more disturbed area around it, about 33 acres, but the quarry itself is 23 acres. We take the top of that off and then we don't keep on moving. It takes about a year and a half to get everything opened up and then for the next 50 years we're in the same spot. That's the differences. A strip mine, every year you're in a new area, every month you're in a new area. Here, we're in the same spot for 50 years.

Question: : It's definitely a hole that goes down?

Reddy: : It's 900 feet deep. And it's a quarry. This is the definition of a quarry.

Question: : The same as you would see in West Rutland at one of those old quarries?

Reddy: : One hole that you open up and you stay there for a long time. And a strip mine is a continuous process, because you're continuously stripping as you move.

Question: : Along the same line, anyone who lives nearby. I don't know if anyone lives within 400 yards or 4 miles of that spot, but anybody near there, that's significantly going to change the environment. The quiet countryside.

Reddy: : There is some noise associated with it and that's part of what we. I hate to give examples from other states, but I have to give examples from what I know. We recently permitted an operation in Arizona. We're approximately one mile from the end of a national wilderness area. National wilderness areas are areas where you're not allowed to have motorized vehicles of any sort. National wilderness areas are very strict. We're about a mile from the border and we had to do a sound study. Everything is site-specific and noise will travel differently, but this is in a valley and we were limited to, I forget how many decibels from our operation. But from the edge of the national wilderness area, I remember the delta, but we actually measured, which was well within that range, was 2 decibels. When we were quiet in this room and we just heard the buzzing in the room, I think in this room you're at 40-50 decibels with just our breath. We have to do exactly the same studies here. That's part of what we're going to be doing, is modeling. The quarry in South Wallingford, that's a similar size to the quarry we'll be doing.

Question: : There are people down there who object.

Reddy: : You must have gone by the there, that's the level of noise there is. That gives you some feel for the kind of operation that goes on.

Question: : How important is the new quarry down in Danby?

Reddy: : The Jobe Phillips Quarry. It's very important. As I've mentioned earlier, one of the problems we have is we have very demanding customers. They constantly want better and better quality because they're trying to have better printing on their magazines ... and this deposit down there is a very good quality deposit. I mean, this is good calcium carbonate. High brightness. It has very low, what's called yellow index. You can have a high brightness, but it may have a little bit - the impurity in it is iron oxide, the staining that you'll see in marble sometimes causes the paper not to look white. It might still be bright, but it'll have a little buffy tint to it.

Question: : That's why when you go into buy paper they've got bright-bright, bright-white, super-bright.

Reddy: : Anybody that has a magazine, that's doing advertising, when they want to have a red flower in the ad, they want it to be red, and the way to get a red flower is you print it on a light background. Advertising is a driver of the paper business. The advertisers want high and higher quality and the paper companies are constantly striving for higher quality, so we have to be opening high quality deposits. You can't have low quality. This is a very good deposit.

Question: : Do you find that the process you have to go through to open this quarry, let's say, is different than the process elsewhere? Our impression would be that it's more involved and more difficult for business here.

Reddy: : I've only been here since May 1, so I'm relatively new to Vermont. I'm learning. I've worked in permitting processes in Florida, Arizona, Illinois and California, and everybody has a process similar to this. And, in addition, in some of the other states ? we're also in national forests, big recreation areas. We have two quarries in one national forest in California that's the most heavily visited national forest in the United States. So you have not only the environmental sensitivity, you have the visual and you get a lot of recreational activity in your area. There are lots of layers of government you have to deal with to make sure you do everything correctly. Is the process here more difficult or different? I don't know yet. All I can say so far is it's similar. You have to go through all the same steps. Everybody wants to make sure you're handling the environment correctly, you've analyzed the visual impacts, everybody's concerned about water, everybody's concerned about air, everybody's very concerned about safety. Vermont is concerned about all the same things, but whether it's more stringent, less stringent, I honestly can't answer that yet.

Question: : One of the complaints about Vermont's process has been that it's not centralized enough.

Reddy: : I guess the only comment I can make is that up until now, in places that I've worked outside of Vermont, you didn't have (to go to) each town and explain the operation, but there was similar processes. But we still wanted to be open with everybody. I'd rather talk to people beforehand, so we still had meetings with people and brought in people from the community and had open houses to find out, OK here's what's going on. So it wasn't formalized. That's different in Vermont. Question: : Is there a timetable for the Danby operation?

Reddy: : What I'd like to do is have the consultants' reports all in sometime late this fall. But we've told them specifically, don't go to any artificial deadline. If something else pops up - when you tell somebody to open up your mind and look at all the possibilities, then you can't tell them, 'well close your mind and here's the deadline.' You have to be honest with them. So we told them, 'here's the target, but if something crops up and you want to look at something else, just give me a call and I'll say OK, and just keep on going.' I'd like to have them in late in the fall, but if we don't get them in then we don't get them in. I'd rather they took the extra time and we made sure that we didn't miss something, so that we get the best information before we submit the permit. If they come in sometime in the late fall, it will take us a while to compile it, to put it together in the form you submit in your Act 250 permits. We'd like to meet with some of the people in some of the towns and present what we're proposing. But the permit application wouldn't go in until spring probably. That's optimistic. We're in a bit of a long process.

Question: : That's more or less like the courts.

Reddy: : Once it gets into the process, then I can't predict how long it'll take.

Question: : On another note, do you perceive that the company's had an image problem, a problem with public relations in the past?

Reddy: : Yes and no. The goal of a company, of course, is to try to grow and we're a private company. You have advantages and disadvantages in a private company. One of the advantages is you can kind of keep your competitors in the dark as to what's going on. There are not a lot of published reports, so they don't know how big you are, they don't know where you're building new plants until all of a sudden it's there. You're not worried about your stock price, so you're not pumping up the company all the time. So you can grow without your competitors sometime knowing that you're growing. They don't know all your customers; they don't know where you are. And that has been for a long time the philosophy of the company: 'Let's try to keep a low profile so our competitors don't know what we're doing.' That's the goal. And it worked pretty well. But situations change, times change. In California, our competitors knew what we were doing because they were a mile down the road ? and we handled things a little bit differently out in the West because we didn't have to worry about being so secretive. We were much more outgoing and public out there because we didn't have to worry about the competitors. We sponsored all the Little League teams and things in the community. If we did it, we let people know who we were. We're going to do the same thing here now. We've been doing a lot of that stuff here; we just didn't let anybody know. If we donated something, it was always, 'OK, here's a donation for the Boy Scouts, but don't tell anybody it came from us,' because we didn't want our competitors to know. OK, we've grown, times have changed, it's time to worry about other things besides our competitors. Our competitors now have pretty much figured out who we are. But with the Internet and everything, our competitors now know what's going on with us, so it's time to change our mode. That's the reason I'm here today. We'd like the community to know what it is we do, what it is we make, what the products are used for. We're going to get more people to see the plant and what's going on there. And when we sponsor a baseball team, we're not going to be afraid to have the name OMYA on the back of the jersey. What we're been doing for a hundred years has worked pretty well. We got very big. But the world changes. We'll change.